At long last, we (libi striegl and Lori Emerson) are ready to send our pamphlet, Build Your Own Mini FM Transmitter, off to the printer! This is the first in a series of pamphlets we’re calling Other Networks for Everyone. We wrote, designed, published, and are now distributing it ourselves in conjunction with the Media Archaeology Lab we run. In short, this is a pamphlet that so clearly walks you through how to build a mini FM transmitter that anyone, especially folks without any electronics experience at all, will be able to follow along. You also do not need a license (at least in the U.S.) because its broadcasting range is no more than 100 feet. The introduction to the pamphlet, including details on how it came to be, is below.

MORE IMPORTANTLY: add your name and email to our list and we’ll contact you for your mailing address once our booklets are ready to ship. Donations are appreciated but not necessary. We believe in our project so much that we would like to mail this to anyone and everyone; we will also make a pdf available. That said, if you’d like a guideline for a donation, it costs roughly $7 to print and mail from the U.S. and roughly $10 to mail internationally. Link to the lab’s support fund is here. Thank you for sharing our enthusiasm for DIY networks!

*

1. What are Other Networks and Why Do We Need Them?

It is no longer debatable to declare: the network we call “the internet” is not the network we want nor the network we deserve. Over the past thirty years or so, the Web has unquestionably devolved into the only network most of us know about and therefore one that most of us accept will ruthlessly track, surveil, and, in Cory Doctorow’s works, increasingly become a place of “enshittification.” The Web is also now one of many networks–including Bluetooth, Wi-Fi, and cellular–we have little to no sense of how it works. For example, how many everyday users know that the Web is only one of many networks that make up an internet we call “the internet”? Or, how many know that radio is integral to nearly every network we use? How many even know how radio waves work?

“Other Networks,” then, is a cluster of projects I have been working on for some years, often in collaboration with the irreplaceable libi striegl, to uncover, document, archive, and experiment with networks that existed before the internet or networks that currently exist outside of this internet. The goal of these projects is not only to significantly expand the historical record. The goal is also to make this knowledge about other networks accessible so that we may begin to reimagine what might be possible in the future. What networks can we bring back to life? What networks can we create?

In this spirit of accessibility, especially for those with no background whatsoever in electronics or radio, this pamphlet is the first of many to come in a series we call “Other Networks For Everyone.” While there are many possible iterations of an other network that is relatively easy to build, we have become increasingly convinced that we haven’t yet begun to tap the potential of amateur radio. Since its inception in the early 20th century, nearly all of the discourse in and around amateur radio is dominated by a forbidding aura of expertise that seems intent on making radio as mysterious and as inaccessible as possible. One could easily say this was a radio priesthood that laid the groundwork for what Byte magazine called in 1976 the “software priesthood”–a movement in computing that encouraged users to stop opening up their machines to understand how they work and instead treat them as if they’re simple, household appliances that one need not understand.

2. Micro-Broadcasting as an Other Network

Coincidentally or not, at the same time as this “software priesthood” emerged in the 1970s, there was a move that began in Europe toward experimenting with micro-broadcasting. ‘Microbroadcasting’ is often used interchangeably with ‘micro-radio,’ ‘miniFM’, and sometimes even ‘free radio’. These are a collection of practices involving the use of a low power transmitter (either as an aesthetic or political choice or out of necessity) over a limited distance and thus reaching a limited number of people. It is also considered a type of “community media” because of its local and non-commercial nature. Given the low power (as much as 100 watts but often as low as 1 watt) and short distances involved (as much as five kilometers from the transmitter but often much shorter), microbroadcasting can be both unlicensed and legal. However, regulations determining the legal status and power of microbroadcasting vary significantly over time and from country to country; if national regulatory bodies prohibit individuals from transmitting to their local community, microbroadcasting may turn into pirate radio. The fact that regulatory bodies determine whether and how microbroadcasting is legal means it is not a practice determined strictly by the constraints of one’s transmitter. Rather, as Tetsuo Kogawa writes in “A Micro Radio Manifesto,” “micro means diverse, multiple, and polymorphous. If micro does not mean small in physical size, then even physically bigger radio station [sic] could become micro. Micro radio is an alternative to mass medium and global communications that could cover the globe with the qualitatively same and patterned information.” Microbroadcasting is therefore primarily a social practice aimed at providing diverse points of view while also resisting the commodification of these points of view and thus its origins can be traced to specific forms of media activism rather than, for example, early wireless radio experiments with low power over short distances.

Based in Bologna, Italy, and lasting from 1976 to 1981, the unlicensed radio station Radio Alice was likely the first instance of microbroadcasting as defined above. Even though it was referred to as “free radio” and pre-dated the emergence of the term “microbroadcasting,” its main founders (students/activists Franco “Bifo” Berardi, Maurizio Torrealta, Filippo Scòzzari, Paolo Ricci, and Carlo Rovelli) essentionally envisioned Radio Alice as a conscious micro radio experiment that sought to distribute control of the airwaves across many small transmitters as a way to flatten hierarchies between sender and receiver, embrace localism, and use art to unsettle if not unseat capitalism. As the editors of the Toronto-based magazine The Red Menace described it in 1978, “Radio Alice broadcast news of the events as they occured, often by airing telephone calls from militants who described events, called for assistance in a given sector, and reported police movements. The station was twice raided and closed down by police, but resumed broadcasting by switching locations and resorting to a transmitter powered by a car battery.” A few years later, in the early 1980s, Tetsuo Kogawa introduced free radio to Japan, calling it “miniFM” as he led the way to hand-building tiny FM transmitters that used less than a hundred milliwatts and only had a half mile radius. The term “micro-radio” or “micro-broadcasting” then emerged in the U.S. in 1983 in the wake of the police beating and blinding African American Dwayne Readus, who changed his name to Mbanna Kantako, in a public housing development in Springfield, Illinois. Kantako first created the Tenants Rights Association (TRA) and, to make sure the TRA could reach as many residents of the development as possible, he created radio station WTRA using a one watt transmitter and broadcast from his living room. In 1988, WTRA became Zoom Black Magic Liberation Radio then Black Liberation Radio followed by Human Rights Radio.

3. Simplifying “the simplest radio broadcaster”

As we learned more about micro-broadcasting and the untapped potential of amateur radio, we eventually realized that, if we wanted to begin the slow, arduous work of getting others involved in probing the limits and possibilities of radio, we needed to get licenses ourselves. We then spent several months attending an online class aimed at increasing the number of women and people of color with amateur radio licenses–a class which we appreciated but which we found was still unwittingly geared to those with an engineering background. After receiving our licenses in January 2023, we resolved to teach classes and workshops for anyone outside of engineering in a way that explained electronics and radio from the ground up.

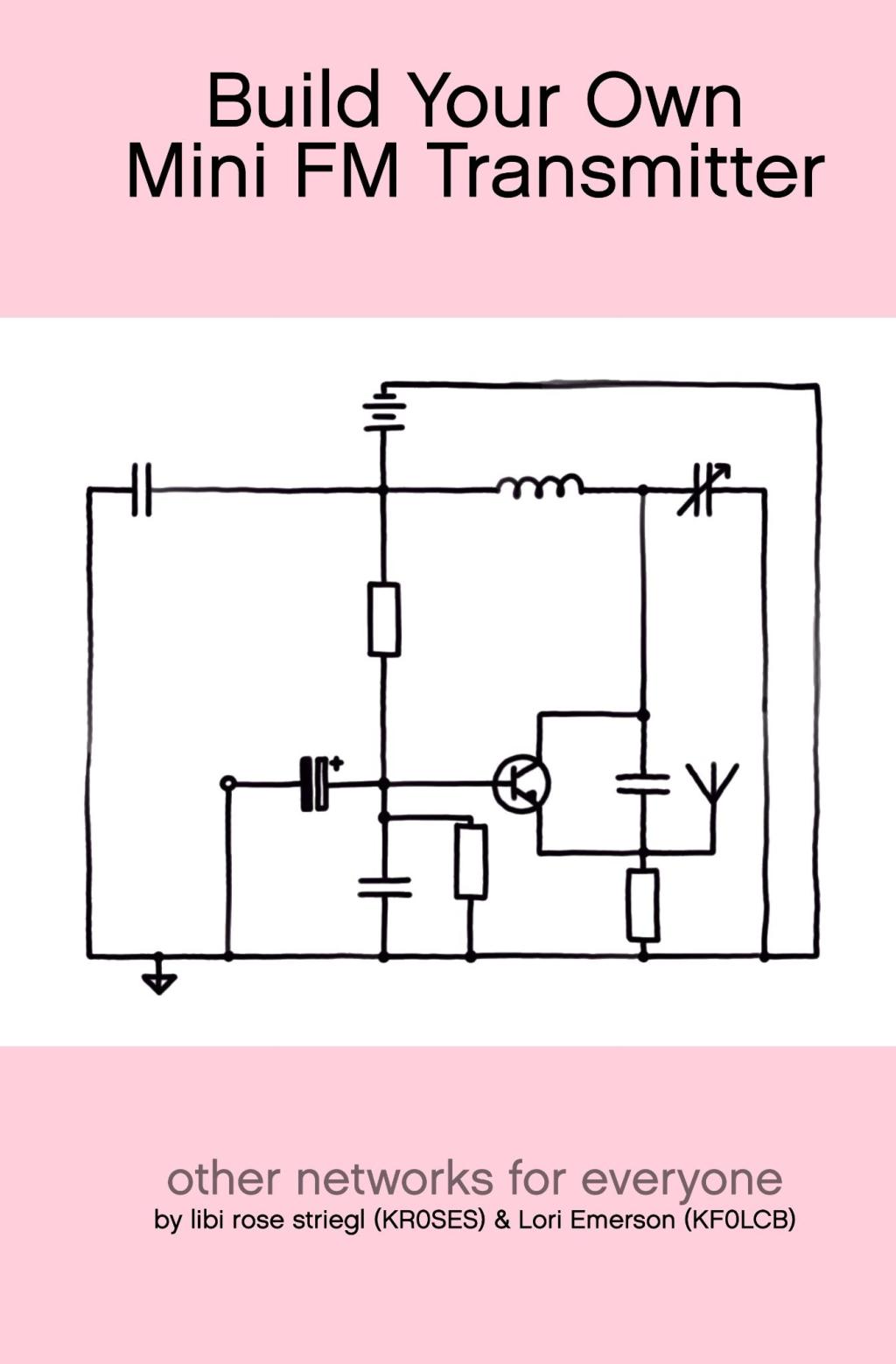

Fortuitously, we had the opportunity to test run a radio workshop in May 2023 when Darren Wershler invited us to help teach a graduate seminar at Concordia University (Montreal, Canada) on maintenance, repair, and sustainability. The class met on Zoom for a week to discuss readings and we then met in person for a week to work on projects related to the theme of the class. libi and I volunteered to lead a project whereby students would have the opportunity to build mini FM transmitters by following Tetsuo Kogawa’s instructions for “the simplest radio transmitter.” What we discovered, however, was that the instructions were far from simple, especially for those who had no experience with electronics. Some of the problems that students encountered: the instructions did not include a schematic so much as they included a diagram that contradicted itself in places; the original circuit was for a transistor that is not readily available outside of Japan and the instructions for an alternative transistor were confusing; there were inconsistent values on resistors and capacitors and no clear instruction on how to determine appropriate substitutions; and, finally, it was not clear that the copper plates in the design needed to be insulated from each other, causing a short in the circuit.

Once libi and I returned home, we spent the next six months crafting a new set of instructions for building a mini FM transmitter that builds on Kogawa’s instructions and is as clear, thorough, and accessible as possible. We hope this encourages many others to feel empowered to experiment with this powerful example of an other network that is for everyone.

Sources: David J. Hess and Robert Gottlieb, Localist Movements in a Global Economy: Sustainability, Justice, and Urban Development in the United States (MIT Press, 2009); Tetsuo Kogawa, “A Micro Radio Manifesto,” Polymorphous Space website (2002, 2006); Marco Briziarelli, “Tripping Down the (Media) Rabbit Hole: Radio Alice and the Insurgent Socialization of Airwaves,” Journal of Radio & Audio Media, 23:2 (October 2016); “Radio Alice: Radio in Action in Italy, The Red Menace 2:2 (Spring 1978); Tetsuo Kogawa, “Toward Polymorphous Radio,” Daina Augaitis and Dan Lander Eds., Radio Rethink : Art Sound and Transmission (Walter Phillips Gallery, 1994); Lawrence Soley, Free Radio: Electronic Civil Disobedience (Routledge, 2018); Steven O. Shields and Robert Ogles, “Black Liberation Radio: A Case Study of Free Radio Micro-broadcasting,” Howard Journal of Communications 5 (1995); Andy Opel, Micro Radio and the FCC: Media Activism and the Struggle over Broadcast Policy (Praeger, 2004); Christina Dunbar-Hester, “Spectral Utopias: Community Radio in the United States, 1970 to Present,” Historia Actual Online, 54:1 (2021); Christina Dunbar-Hester, Low Power to the People: Pirates, Protest and Politics in FM Radio Activism (MIT Press, 2014)

Leave a reply to John Schuch Cancel reply